Northern Namibia

November 20th - December 4th, 1999

We left Drotksy's early in the morning, but not before engaging the owners

in a discussion about the storm

of the previous evening and the damage they sustained. They warned us

to be careful on the highway, as a couple who had left the day before had

their vacation dramatically shortened when they collided with a buffalo

grazing on the road. They were ok and were able to limp their mangled truck

home, but it came as a shock as we just had dinner with them two nights

before and they had that same vacation/explorer glow that we walk around

with. If it can happen to them, it can happen to us.

Interestingly, our feelings of mortality co-incided with our first foray

of the trip into a recently active war zone: Namibia's Caprivi strip. While

we were in Morocco we had heard of rebel uprisings over our shortwave radio

and how the Namibian government quickly squashed them and were now "interrogating"

the ringleaders in some dark hellhole of a prison. The region has been quiet

since then, and other tourons coming from there confirm that all is cool.

Caprivi is an interesting artifact of the colonial chess match waged

in the 19th century in Africa. The strip was tacked onto Namibia when they

called this area SouthWest Africa and it was under the colonial thumb of

the Germans. The Germans got it in a swap with the English; the Brits got

Zanzibar and the Germans got Caprivi and some insignificant seagull nest

of an island in the North Sea off the coast of Germany. Had logic prevailed,

this strip of land would have gone to Botswana, Angola or Zambia, but now

gives Namibia its only well watered and productive farmland.

We had gotten a glimpse of the Caprivi when at Chobe, and all we saw

were cabbage and cattle. Since this strip is Namibia's sole usable farmland,

it has been developed to the hilt and almost all the wildlife is gone. Not

prime touring material. Once we got through the laughably small border crossing

(a desk, a picnic table and a manually opened chain link road gate), we

shot through Caprivi and only stopped when we hit the town of Rundu near

the Angolan border, where we overnighted.

Rundu itself is one of those supply towns, providing modern services

and goods to Caprivi and the undeveloped northwest Namibian corner. We got

our first taste of what it means to be in Namibia on a Sunday when we found

the town deserted and we had to scrounge for supplies at the Shell's stations

meager larder. Desperately poor Africans hang out at the service station,

buzzing around you like flies. We share a package of crackers with some

children (we've decided the adults are a lost cause and only help children)

and head south.

Postscript: It turns out that when

we were in Rundu, Namibia had covertly given permission for the Angolan

government to conduct operations against rebels that were using Namibia

as their base. At a service station we saw a left-hand drive jeep-type vehicle

with four people in fatigues that gave us the once over and then continued

with their business -- they must have been part of the Angolan force. The

whole region has since destabilized and now both civilians and tourists

have been killed. Namibia is talking about calling up men into the army

and is preparing to wage war with UNITA and Jonas Savimbi, the best bush

fighter in the world. Tourists are giving Namibia a wide berth and it's

anyone's guess what will happen next.

Hoba Meteor

As we leave Rundu, our plans (as usual) are ill-formed. Not

a problem, as all reasonable roads leading from the Caprivi head for a trinity

of Namibian towns: Grootfontein, Tsumeb, and Otavi. We've heard good things

about each and our curious ourselves about which one we'll stay at first.

Our big problem is that our first day exploring Namibia is a Sunday. As

Namibia was once a German colony and to this day retains not only the German

language but most of the old German customs, Sunday is the day of rest.

Period. The only thing you'll find open in Namibia on a Sunday is some of

the petrol stations. This makes it tough to suss out a town, and was our

first introduction to what the locals mean when they say "Namibia is

more German than Germany."

As we leave Rundu, our plans (as usual) are ill-formed. Not

a problem, as all reasonable roads leading from the Caprivi head for a trinity

of Namibian towns: Grootfontein, Tsumeb, and Otavi. We've heard good things

about each and our curious ourselves about which one we'll stay at first.

Our big problem is that our first day exploring Namibia is a Sunday. As

Namibia was once a German colony and to this day retains not only the German

language but most of the old German customs, Sunday is the day of rest.

Period. The only thing you'll find open in Namibia on a Sunday is some of

the petrol stations. This makes it tough to suss out a town, and was our

first introduction to what the locals mean when they say "Namibia is

more German than Germany."

We visit the first town one reaches from the Caprivi, Grootfontein, and

find it closed. Shame, as we hear it's a town geared for tourists and is

a nice experience. Undaunted, we decide to head for our second choice of

the trinity, Tsumeb, and while bombing down the road we see the turnoff

for the Hoba Meteor. Having been occasionally accused of being of alien

origins, we can't pass up the real thing and head down the seventeen kilometers

of dirt road to see the largest known meteor to strike the Earth.

We have to admit, we thought we would see craters, ejecta and such before

we actually arrived at the site of the metor. After all, the world's largest

meteor should leave a pretty big dent, right? It was with great surprise

that we drove along a perfectly normal dirt road passing by perfectly normal

ranchland until we came upon the turn for the meteor. After paying our entrance

fee were told that "yes, it's just a short walk this way." Odd.

We walked along a short and groomed path and came upon a

small amphitheater centered upon this huge piece of iron. Weighing at sixty

tons, the Hoba meteor does indeed look like all those meteors you see in

the museums, just a lot larger. Technically an ataxite, it's believed that

Hoba was part of a much larger asteroid that hit the Earth 80,000 years

ago.

We walked along a short and groomed path and came upon a

small amphitheater centered upon this huge piece of iron. Weighing at sixty

tons, the Hoba meteor does indeed look like all those meteors you see in

the museums, just a lot larger. Technically an ataxite, it's believed that

Hoba was part of a much larger asteroid that hit the Earth 80,000 years

ago.

Found by a hunter in the 1920's, the meteor for a long time was only

known by "insiders", many of whom chopped off little pieces with

their hacksaws for their souvenir collection. Declared a national monument

in 1955, the odd cuboid shape of the meteor suggests that there are other

hunks of the original asteroid that await discovery.

We left Hoba amazed that 80,000 years was long enough to weather away

the impact crater that the meteor left upon this little corner of Africa.

Perhaps it's our preconception of the desert and other arid lands as static

places, but we left with an understanding of how dynamic Namibian ecology

and geology must be.

Tsumeb

Continuing on to Tsumeb, we found a town only slightly more

open than the last one. We were able to stock up on some basic foodstuffs

and beer before grabbing a campsite in the town's caravan park and weathering

a rainy evening. The next day we treat ourselves to a room in town in celebration

of Kathy's birthday and spend the day touring the town's sights. Tsumeb

has seen fatter days, back when the town's mine was open. Seems that Tsumeb

is located on top of a gigantic plume of copper, lead and other metals.

Tsumeb once provided much of the world's supply of these metals, and is

the sole location of a number of mineral composites. The mines survived

the crash in copper and other metal prices, only to go bankrupt three years

ago when a prolonged strike forced unsustainable labor costs upon it. Many

other businesses, dependent upon the money mining brought into town, have

also closed rendering Tsumeb a sleepy place on the busiest of days.

Continuing on to Tsumeb, we found a town only slightly more

open than the last one. We were able to stock up on some basic foodstuffs

and beer before grabbing a campsite in the town's caravan park and weathering

a rainy evening. The next day we treat ourselves to a room in town in celebration

of Kathy's birthday and spend the day touring the town's sights. Tsumeb

has seen fatter days, back when the town's mine was open. Seems that Tsumeb

is located on top of a gigantic plume of copper, lead and other metals.

Tsumeb once provided much of the world's supply of these metals, and is

the sole location of a number of mineral composites. The mines survived

the crash in copper and other metal prices, only to go bankrupt three years

ago when a prolonged strike forced unsustainable labor costs upon it. Many

other businesses, dependent upon the money mining brought into town, have

also closed rendering Tsumeb a sleepy place on the busiest of days.

The glory days of Tsumeb are remembered in the its museum,

dedicated to the town's German fathers and the indigenous population they

displaced. Some of our favorite displays were the 19th century steam engine

(left) and the cross section of one of the mine's water pipes that was showing

reduced water flow (right); can you see why?

The glory days of Tsumeb are remembered in the its museum,

dedicated to the town's German fathers and the indigenous population they

displaced. Some of our favorite displays were the 19th century steam engine

(left) and the cross section of one of the mine's water pipes that was showing

reduced water flow (right); can you see why?

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of life in Tsumeb is that peoples'

preferred language is German, even though the German colonial period ended

86 years ago. It's not some odd dialect of German either; it's perfect hoch

Deutsch, or standard high German. Most everyone can speak English and

Afrikaans as well, and the common indigenous languages are by and large

various dialects of Bantu. German, though, is the language that binds them

all. Rather odd being panhandled in German in Africa.

Lake Otjikoto

On the way from Tsumeb to Etosha National Park lies Namibia's two and

only naturally occurring lakes. Actually giant sinkholes that have filled

with water, one lies along our route and was impossible to pass up. Lake

Otjikoto measures 55 meters deep and once provided Tsumeb with all of its

fresh water, pumped the nearly twenty kilometers to town by a grand old

brick and steel German steam pump (currently under restoration). Very impressive,

especially considering it was put together at the end of the 19th century

in the middle of nowhere.

Etosha National Park

We must admit that when we entered Namibia, we thought we would be embarking

on a different phase of the trip. Ever since we left Harare we've been hopping

from game park to game park, camping and gawking at critters. Our guess

it would be a while before we went to another game park, but as we talked

with the locals and fellow travelers, they all said "You must go to

Etosha." Off we went, believing that more animal watching would be

a bit of a yawn, having done exactly that for over a month now. And how

many animals can there be in a brutal desert, after all?

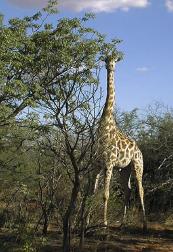

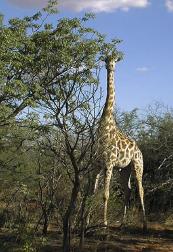

In this place that the desert people of Namibia call hellish we found

a land teeming with more wildlife than you could expect. Our first sighting

was a large herd of giraffe, loping across the hard desert pack. You can't

fully understand the grace of the giraffe until you've seen them running.

Their necks almost seem to swim through the air and their long legs reveal

to you the ballet of the gallop that the fury of a horse's shorter legs

conceal.

New and very striking animals showed themselves on the arid planes. Our

favorite were the gemsboks (pictured above), with big chests, very distinctive

black and white facial patterns, and these unworldly long and pointed horns.

We hear they can go a month without water. Also new to us was the hartebeest

(no good pics, sorry) which gets its name from its reddish hue and its heart-shaped

horns.

Even the campground critters were a trip. We made two buddies

at one campground: this squirrel who had a thing for deep fried peri-peri

corn chips, and a hornbill with a dislocated leg. Twisted halfway around

with what looked like a recent injury, we couldn't imagine that it didn't

hurt. It didn't deter the bird from anything, as we witnessed it swoop in,

grab a ten centimeter baboon spider we were watching near Spot's tire, kill

it, and then proceed to choke it down. Got it with the first grab, too.

Even the campground critters were a trip. We made two buddies

at one campground: this squirrel who had a thing for deep fried peri-peri

corn chips, and a hornbill with a dislocated leg. Twisted halfway around

with what looked like a recent injury, we couldn't imagine that it didn't

hurt. It didn't deter the bird from anything, as we witnessed it swoop in,

grab a ten centimeter baboon spider we were watching near Spot's tire, kill

it, and then proceed to choke it down. Got it with the first grab, too.

Most of the other animals in the African dance also live

in Etosha. Etosha's strain of animals tend to have unique qualities. The

lion here in Etosha is prized by zoos and breeders all around the world

as it is completely free of feline aids, isolated as it is from the rest

of this continent in which aids runs rampant, among the cats as well as

humans. The Namibian elephant has longer legs and needs much less water

than other African elephants.

Most of the other animals in the African dance also live

in Etosha. Etosha's strain of animals tend to have unique qualities. The

lion here in Etosha is prized by zoos and breeders all around the world

as it is completely free of feline aids, isolated as it is from the rest

of this continent in which aids runs rampant, among the cats as well as

humans. The Namibian elephant has longer legs and needs much less water

than other African elephants.

We caught on camera what had eluded us so far this trip: a good shot

of a jackal. Two actually, flushed out when we cruised Spot over the drain

pipe in which they were hiding. One of the animals most wary of humans,

we've only been able to get quick glimpses of them. Not these two; they

waited until we drove away to get back in their hidey-hole.

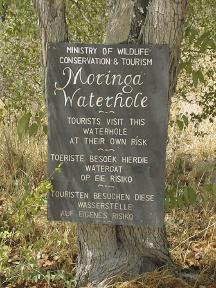

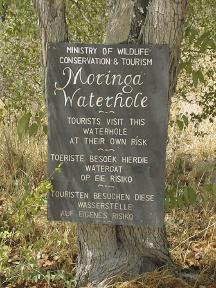

Moringa Waterhole

While visiting Etosha and viewing it in the manner that we've

seen other game parks would have been most pleasant and rewarding, the touch

that lifts Etosha from being a good game park to being one of the world's

best is its three waterholes, Okaukuejo, King Nehale, and Moringa. On the

edge of its three main campgrounds, these permanent waterholes serve as

magnets for animals and tourists alike and allows an unfettered, up-front

and unrivaled view of African wildlife.

While visiting Etosha and viewing it in the manner that we've

seen other game parks would have been most pleasant and rewarding, the touch

that lifts Etosha from being a good game park to being one of the world's

best is its three waterholes, Okaukuejo, King Nehale, and Moringa. On the

edge of its three main campgrounds, these permanent waterholes serve as

magnets for animals and tourists alike and allows an unfettered, up-front

and unrivaled view of African wildlife.

What makes the Etosha waterhole experiences unique is that you can watch

the wildlife safely at night. Every wildlife park we've visited in Africa

so far close the gates of their campgrounds at sunset and don't unlock them

until sunrise, so it's impossible to view wildlife at night. Etosha's waterholes

are adjacent to the main campgrounds and never close, so you can wander

over any time of day or night and check out the scene. Nocturnal species

that normally are so difficult to spot trot right out on main stage, eye

the crowd warily, and then take a nice, long drink.

Our favorite was Moringa Waterhole in the Halalie campgrounds. With the

rainy season just beginning, groundwater levels are so low that Etosha's

animals have very few choices on where to get a drink. Moringa is the only

water around for at least fifty kilometers, so during the dry winter all

the animals in the area must, sooner or later, come here.

A few rains have already kissed Namibia, so the most shy of African wildlife

can minimize the number of visits they must make to the waterholes. Our

leopard still eludes us, but just about everything else made a visit to

Moringa, including several rhino families. As the rains have taken the edge

off of most of the animals' thirst, the natural pecking order now applies

at the waterholes. One rhino family, obviously anxious for water, waited

at a distance for over half an hour while a group of elephants lingered

over a drink. Even sending the smallest and least threatening rhino cub

forward elicited an unmistakable "get back" message from the elephants.

We didn't realize it until actually seeing the waterhole, but we've seen

video of Moringa on PBS nature shows. Taken during one winter during the

drought years of the early nineties, normal animal behavior had completely

broken down and lions, leopards and their normal prey animals drank side

by side, driven together by their common thirst. There seems to be a seldom

broken law that predators won't attack prey near these waterholes.

On our second visit to Etosha we witnessed

this elephant fight to the right. The battle was over who got to drink from

the "sweet spot" where the water comes right from the spigot.

We were of the impression that for these two elephants this has been brewing

for a while and waterhole was just the spark.

On our second visit to Etosha we witnessed

this elephant fight to the right. The battle was over who got to drink from

the "sweet spot" where the water comes right from the spigot.

We were of the impression that for these two elephants this has been brewing

for a while and waterhole was just the spark.

Finally, we found the Okaukuejo waterhole to also offer quality wildlife

viewing. The place to spy rhinos, the waterhole is ringed by huts and rondavels

making for a crowded evening's viewing. Just before midnight, though, everyone

turns in and it's just you and the rhinos. The last waterhole, King Nehale

in Namutoni campgrounds, is mostly filled with reeds and while it makes

for nice bird and frog watching, it attracts few large animals.

Our second visit was twice fortunate

for us, as we were able to meet Fritz the German, a wildlife biologist who's

been coming to Namibia for over ten years now, staying months at a time.

He tours the wilds here with the Cadillac of the 4WD club here: a Unimog

(oo-nee-mach). Built by Mercedes for use as a tractor, the Unimog has an

incredible ground clearance using offset axles similar to the Hummvee. Fritz

here has outfitted his as a mobile research lab and crashpad. Teutonic in

perfection, his Unimog allows him to be completely self-sufficient for several

weeks at a time.

Our second visit was twice fortunate

for us, as we were able to meet Fritz the German, a wildlife biologist who's

been coming to Namibia for over ten years now, staying months at a time.

He tours the wilds here with the Cadillac of the 4WD club here: a Unimog

(oo-nee-mach). Built by Mercedes for use as a tractor, the Unimog has an

incredible ground clearance using offset axles similar to the Hummvee. Fritz

here has outfitted his as a mobile research lab and crashpad. Teutonic in

perfection, his Unimog allows him to be completely self-sufficient for several

weeks at a time.

We've seen a few of these Unimogs here, and more than one of them have

been outfitted as mobile bachelor pads. It makes perfect sense; your apartment

on wheels that can go anywhere in Africa.

Outjo

Outjo will always be memorable in our minds as it's the city

where our first major truck trauma

happened. Our rear axle crapped out, which meant that we could only move

the truck by engaging 4WD and dragging it around on the front axle. We take

it to a mechanic and find the flange fitted to one sides' axle shaft has

worn all of its gear splines clean off. The other side is bad too, so we

order parts but they're going to take a week to arrive. We get the flange

and axle shaft welded together and take it easy, with no four-wheeling or

high speeds until we get it fixed. At least our campground had a stress-reducing

pet kudu you could play with. Most of the good rubs that work with cats

work with kudus, although they do make problematic lap pets.

Outjo will always be memorable in our minds as it's the city

where our first major truck trauma

happened. Our rear axle crapped out, which meant that we could only move

the truck by engaging 4WD and dragging it around on the front axle. We take

it to a mechanic and find the flange fitted to one sides' axle shaft has

worn all of its gear splines clean off. The other side is bad too, so we

order parts but they're going to take a week to arrive. We get the flange

and axle shaft welded together and take it easy, with no four-wheeling or

high speeds until we get it fixed. At least our campground had a stress-reducing

pet kudu you could play with. Most of the good rubs that work with cats

work with kudus, although they do make problematic lap pets.

At least the axle incident allowed us a second chance to visit Etosha

and see the change a big rainstorm brings. Animal sightings at the waterholes

decreased dramatically, and the foliage was noticeably denser than before

making spotting the critters in the bush very difficult. Made it all too

obvious why many people visit southern Africa in the dry winter season.

Waterberg Plateau

After Etosha, we stay one last rainy night in Outjo and the

next morning take Spot to the mechanics to have our new axle shafts and

flanges fitted. Fully mobile once again, we shoot straight south on the

road to the capitol of Namibia, Windhoek. We break up the trip with a visit

to Waterberg Plateau with the idea of checking it out for a night and staying

if we like it. We arrived just before the rain gods opened the zipper and

made an already muddy park soaking wet (our campground to the right).

After Etosha, we stay one last rainy night in Outjo and the

next morning take Spot to the mechanics to have our new axle shafts and

flanges fitted. Fully mobile once again, we shoot straight south on the

road to the capitol of Namibia, Windhoek. We break up the trip with a visit

to Waterberg Plateau with the idea of checking it out for a night and staying

if we like it. We arrived just before the rain gods opened the zipper and

made an already muddy park soaking wet (our campground to the right).

We have to admit that had it been raining when we arrived we might have

skipped the park altogether. However, since the fifty kilometer long unbroken

line of the plateau has us hooked (and we've paid our gate fee) we're staying.

Days like this we just grab a book, hop in the tent and wait for the rain

to end. Between yesterday's and today's rains, Waterberg has seen almost

a third of its annual rainfall. It did stop during the afternoon, and left

us with beautifully mottled clouds for sunset.

That evening the rain gave birth to millions of winged bugs. In their

annual mating dance, they filled the skies and the ground. Lizards abounded

everywhere, gulping them down like potato chips. The piles of bugs everywhere

were simply incredible.

We were awed at the speed at which

this arid land drank up the water. By the next morning almost all the standing

water was gone, and the hot sun baked once again. We decided to hike to

the top of the plateau and to the beginning of the 42 kilometer long distance

permit trail. The path to the top (photo left) was a bit challenging but

nothing technical, and the view offered of the surrounding pancake terrain

was well worth the exertion.

We were awed at the speed at which

this arid land drank up the water. By the next morning almost all the standing

water was gone, and the hot sun baked once again. We decided to hike to

the top of the plateau and to the beginning of the 42 kilometer long distance

permit trail. The path to the top (photo left) was a bit challenging but

nothing technical, and the view offered of the surrounding pancake terrain

was well worth the exertion.

Despite not having trail permits, we decide to venture into the back

country unescorted for a few kilometers. The reddish sandstone rock found

at Waterberg weathers in odd ways, with columns and arches to be found all

around. Plants and animals integrate themselves within all the rock niches,

as shown by this fig tree to the right. This trail is only open between

April and November, and would make a delightful four day hike.

Adjacent to the campgrounds were an old German military graveyard

and a delightful aloe tree forest. Awakened by this week's rains, the forest

was populated with all sorts of insects. We found our first dung beetles

here at Waterberg, and found the manner they go about their work fascinating.

Bright red bugs crawled all across the paths like little Martians.

Adjacent to the campgrounds were an old German military graveyard

and a delightful aloe tree forest. Awakened by this week's rains, the forest

was populated with all sorts of insects. We found our first dung beetles

here at Waterberg, and found the manner they go about their work fascinating.

Bright red bugs crawled all across the paths like little Martians.

Finally, on our last full day in Waterberg we took a drive

with one of the park's rangers to the opposite side of the plateau. With

no camping allowed, the game have this section of the park all to themselves.

We saw much more of the odd rock formations we found during our hikes near

camp, and viewed much of the park's larger animals. Although they were introduced

into the parks in the days Waterberg was administered by South Africa, giraffes

now make Waterberg their home and blend in well with the plateau's veld.

Finally, on our last full day in Waterberg we took a drive

with one of the park's rangers to the opposite side of the plateau. With

no camping allowed, the game have this section of the park all to themselves.

We saw much more of the odd rock formations we found during our hikes near

camp, and viewed much of the park's larger animals. Although they were introduced

into the parks in the days Waterberg was administered by South Africa, giraffes

now make Waterberg their home and blend in well with the plateau's veld.

As we leave Rundu, our plans (as usual) are ill-formed. Not

a problem, as all reasonable roads leading from the Caprivi head for a trinity

of Namibian towns: Grootfontein, Tsumeb, and Otavi. We've heard good things

about each and our curious ourselves about which one we'll stay at first.

Our big problem is that our first day exploring Namibia is a Sunday. As

Namibia was once a German colony and to this day retains not only the German

language but most of the old German customs, Sunday is the day of rest.

Period. The only thing you'll find open in Namibia on a Sunday is some of

the petrol stations. This makes it tough to suss out a town, and was our

first introduction to what the locals mean when they say "Namibia is

more German than Germany."

As we leave Rundu, our plans (as usual) are ill-formed. Not

a problem, as all reasonable roads leading from the Caprivi head for a trinity

of Namibian towns: Grootfontein, Tsumeb, and Otavi. We've heard good things

about each and our curious ourselves about which one we'll stay at first.

Our big problem is that our first day exploring Namibia is a Sunday. As

Namibia was once a German colony and to this day retains not only the German

language but most of the old German customs, Sunday is the day of rest.

Period. The only thing you'll find open in Namibia on a Sunday is some of

the petrol stations. This makes it tough to suss out a town, and was our

first introduction to what the locals mean when they say "Namibia is

more German than Germany." We walked along a short and groomed path and came upon a

small amphitheater centered upon this huge piece of iron. Weighing at sixty

tons, the Hoba meteor does indeed look like all those meteors you see in

the museums, just a lot larger. Technically an ataxite, it's believed that

Hoba was part of a much larger asteroid that hit the Earth 80,000 years

ago.

We walked along a short and groomed path and came upon a

small amphitheater centered upon this huge piece of iron. Weighing at sixty

tons, the Hoba meteor does indeed look like all those meteors you see in

the museums, just a lot larger. Technically an ataxite, it's believed that

Hoba was part of a much larger asteroid that hit the Earth 80,000 years

ago. Continuing on to Tsumeb, we found a town only slightly more

open than the last one. We were able to stock up on some basic foodstuffs

and beer before grabbing a campsite in the town's caravan park and weathering

a rainy evening. The next day we treat ourselves to a room in town in celebration

of Kathy's birthday and spend the day touring the town's sights. Tsumeb

has seen fatter days, back when the town's mine was open. Seems that Tsumeb

is located on top of a gigantic plume of copper, lead and other metals.

Tsumeb once provided much of the world's supply of these metals, and is

the sole location of a number of mineral composites. The mines survived

the crash in copper and other metal prices, only to go bankrupt three years

ago when a prolonged strike forced unsustainable labor costs upon it. Many

other businesses, dependent upon the money mining brought into town, have

also closed rendering Tsumeb a sleepy place on the busiest of days.

Continuing on to Tsumeb, we found a town only slightly more

open than the last one. We were able to stock up on some basic foodstuffs

and beer before grabbing a campsite in the town's caravan park and weathering

a rainy evening. The next day we treat ourselves to a room in town in celebration

of Kathy's birthday and spend the day touring the town's sights. Tsumeb

has seen fatter days, back when the town's mine was open. Seems that Tsumeb

is located on top of a gigantic plume of copper, lead and other metals.

Tsumeb once provided much of the world's supply of these metals, and is

the sole location of a number of mineral composites. The mines survived

the crash in copper and other metal prices, only to go bankrupt three years

ago when a prolonged strike forced unsustainable labor costs upon it. Many

other businesses, dependent upon the money mining brought into town, have

also closed rendering Tsumeb a sleepy place on the busiest of days. The glory days of Tsumeb are remembered in the its museum,

dedicated to the town's German fathers and the indigenous population they

displaced. Some of our favorite displays were the 19th century steam engine

(left) and the cross section of one of the mine's water pipes that was showing

reduced water flow (right); can you see why?

The glory days of Tsumeb are remembered in the its museum,

dedicated to the town's German fathers and the indigenous population they

displaced. Some of our favorite displays were the 19th century steam engine

(left) and the cross section of one of the mine's water pipes that was showing

reduced water flow (right); can you see why?

Even the campground critters were a trip. We made two buddies

at one campground: this squirrel who had a thing for deep fried peri-peri

corn chips, and a hornbill with a dislocated leg. Twisted halfway around

with what looked like a recent injury, we couldn't imagine that it didn't

hurt. It didn't deter the bird from anything, as we witnessed it swoop in,

grab a ten centimeter baboon spider we were watching near Spot's tire, kill

it, and then proceed to choke it down. Got it with the first grab, too.

Even the campground critters were a trip. We made two buddies

at one campground: this squirrel who had a thing for deep fried peri-peri

corn chips, and a hornbill with a dislocated leg. Twisted halfway around

with what looked like a recent injury, we couldn't imagine that it didn't

hurt. It didn't deter the bird from anything, as we witnessed it swoop in,

grab a ten centimeter baboon spider we were watching near Spot's tire, kill

it, and then proceed to choke it down. Got it with the first grab, too. Most of the other animals in the African dance also live

in Etosha. Etosha's strain of animals tend to have unique qualities. The

lion here in Etosha is prized by zoos and breeders all around the world

as it is completely free of feline aids, isolated as it is from the rest

of this continent in which aids runs rampant, among the cats as well as

humans. The Namibian elephant has longer legs and needs much less water

than other African elephants.

Most of the other animals in the African dance also live

in Etosha. Etosha's strain of animals tend to have unique qualities. The

lion here in Etosha is prized by zoos and breeders all around the world

as it is completely free of feline aids, isolated as it is from the rest

of this continent in which aids runs rampant, among the cats as well as

humans. The Namibian elephant has longer legs and needs much less water

than other African elephants.

While visiting Etosha and viewing it in the manner that we've

seen other game parks would have been most pleasant and rewarding, the touch

that lifts Etosha from being a good game park to being one of the world's

best is its three waterholes, Okaukuejo, King Nehale, and Moringa. On the

edge of its three main campgrounds, these permanent waterholes serve as

magnets for animals and tourists alike and allows an unfettered, up-front

and unrivaled view of African wildlife.

While visiting Etosha and viewing it in the manner that we've

seen other game parks would have been most pleasant and rewarding, the touch

that lifts Etosha from being a good game park to being one of the world's

best is its three waterholes, Okaukuejo, King Nehale, and Moringa. On the

edge of its three main campgrounds, these permanent waterholes serve as

magnets for animals and tourists alike and allows an unfettered, up-front

and unrivaled view of African wildlife. On our second visit to Etosha we witnessed

this elephant fight to the right. The battle was over who got to drink from

the "sweet spot" where the water comes right from the spigot.

We were of the impression that for these two elephants this has been brewing

for a while and waterhole was just the spark.

On our second visit to Etosha we witnessed

this elephant fight to the right. The battle was over who got to drink from

the "sweet spot" where the water comes right from the spigot.

We were of the impression that for these two elephants this has been brewing

for a while and waterhole was just the spark.

Outjo will always be memorable in our minds as it's the city

where our

Outjo will always be memorable in our minds as it's the city

where our

After Etosha, we stay one last rainy night in Outjo and the

next morning take Spot to the mechanics to have our new axle shafts and

flanges fitted. Fully mobile once again, we shoot straight south on the

road to the capitol of Namibia, Windhoek. We break up the trip with a visit

to Waterberg Plateau with the idea of checking it out for a night and staying

if we like it. We arrived just before the rain gods opened the zipper and

made an already muddy park soaking wet (our campground to the right).

After Etosha, we stay one last rainy night in Outjo and the

next morning take Spot to the mechanics to have our new axle shafts and

flanges fitted. Fully mobile once again, we shoot straight south on the

road to the capitol of Namibia, Windhoek. We break up the trip with a visit

to Waterberg Plateau with the idea of checking it out for a night and staying

if we like it. We arrived just before the rain gods opened the zipper and

made an already muddy park soaking wet (our campground to the right).

We were awed at the speed at which

this arid land drank up the water. By the next morning almost all the standing

water was gone, and the hot sun baked once again. We decided to hike to

the top of the plateau and to the beginning of the 42 kilometer long distance

permit trail. The path to the top (photo left) was a bit challenging but

nothing technical, and the view offered of the surrounding pancake terrain

was well worth the exertion.

We were awed at the speed at which

this arid land drank up the water. By the next morning almost all the standing

water was gone, and the hot sun baked once again. We decided to hike to

the top of the plateau and to the beginning of the 42 kilometer long distance

permit trail. The path to the top (photo left) was a bit challenging but

nothing technical, and the view offered of the surrounding pancake terrain

was well worth the exertion. Adjacent to the campgrounds were an old German military graveyard

and a delightful aloe tree forest. Awakened by this week's rains, the forest

was populated with all sorts of insects. We found our first dung beetles

here at Waterberg, and found the manner they go about their work fascinating.

Bright red bugs crawled all across the paths like little Martians.

Adjacent to the campgrounds were an old German military graveyard

and a delightful aloe tree forest. Awakened by this week's rains, the forest

was populated with all sorts of insects. We found our first dung beetles

here at Waterberg, and found the manner they go about their work fascinating.

Bright red bugs crawled all across the paths like little Martians. Finally, on our last full day in Waterberg we took a drive

with one of the park's rangers to the opposite side of the plateau. With

no camping allowed, the game have this section of the park all to themselves.

We saw much more of the odd rock formations we found during our hikes near

camp, and viewed much of the park's larger animals. Although they were introduced

into the parks in the days Waterberg was administered by South Africa, giraffes

now make Waterberg their home and blend in well with the plateau's veld.

Finally, on our last full day in Waterberg we took a drive

with one of the park's rangers to the opposite side of the plateau. With

no camping allowed, the game have this section of the park all to themselves.

We saw much more of the odd rock formations we found during our hikes near

camp, and viewed much of the park's larger animals. Although they were introduced

into the parks in the days Waterberg was administered by South Africa, giraffes

now make Waterberg their home and blend in well with the plateau's veld.