Central Namibia

December 5th - December 17th, 1999

Windhoek

Starting out this Sunday morning we expected a relatively quiet drive as we headed south from Waterberg Plateau, and so it was at the beginning. Fritz had told us about a butchery in Okahandja that sold the best -- no foolin', the best -- biltong in all of southern Africa. Biltong is a dried and seasoned meat that if you say resembles American jerky the locals get all fumed and complain that us Americans couldn't cure meat of boredom. We certainly have enjoyed the biltong we've tried here, and couldn't pass up a chance to taste the best. Frankly though, our hopes aren't very high as it is a Sunday and in Namibia everything is closed on Sunday. Still, we take the turn off for Okahandja, drive down a totally deserted main street, pull into the Namibia Biltong Factory's empty parking lot, try the front door and find that, surprise!, it's unlocked. Beyond all hopes the Factory's store is open for business. Amazed, we pick out a few of the spicier flavors of biltong (peri-peri and BBQ), a couple of cokes, and hit the highway towards Windhoek -- munching on some very fine biltong.

Motor traffic throughout north Namibia has consistently been light and low key, but as we get closer to Windhoek this begins to change. The pace and tempo becomes more frenzied and frantic, reminiscent of South African driving styles, and a clear indication we're approaching an urban center. The center of Windhoek is, however, quiet with all businesses closed (remember, more German than Germany), so we find a backpackers hostel in a neighborhood bordering the city center and go for a short walk to find something to eat. The only open restaurant is the Windhoek Bräuhaus, a German style beer hall ,where we were able to buy a few snacks and have a couple of drinks.

Come Monday morning the city comes back to life again. As

Windhoek is the capitol and the largest city in Namibia, we're a bit taken

aback by how small it is. Apparently only 150,000 people in size, while

Windhoek retains a few traces of its German colonial past, it is really

a small, modern city.

Come Monday morning the city comes back to life again. As

Windhoek is the capitol and the largest city in Namibia, we're a bit taken

aback by how small it is. Apparently only 150,000 people in size, while

Windhoek retains a few traces of its German colonial past, it is really

a small, modern city.

Namibia must have a thing for meteorites, as plopped down

in the center of town is collection of thirty-three of them (photo left).

They fell from the sky together along with a storm of many more near the

south Namibian town of Gibeon.

Namibia must have a thing for meteorites, as plopped down

in the center of town is collection of thirty-three of them (photo left).

They fell from the sky together along with a storm of many more near the

south Namibian town of Gibeon.

One bit of colonial charm left in Windhoek is the Christuskirche. Built in 1907 from local sandstone, it serves as Windhoek's oldest church and an icon of the city. In the process of being restored, we were intrigued to learn that the church is currently searching for the funds to repair its wonderful German stain-glass windows. Seems they were originally installed backwards, with the inside face pointing out (welcome to Africa!) and are in danger of being permanently damaged by weathering. All of them need to be removed, cleaned up and repositioned so that the proper side of the glass faces out. Oooff!

Less than a block away from the Christuskirche is the Alte

Feste, the oldest building in town (1890) and originally the headquarters

of the Schutztruppe, the colonial German defense force. Now the Namibian

State museum, the Alte Feste houses an excellent chronicle of Namibian history

starting just before the country's tenure as a German colony, through the

South African occupation, and ending with the advent of independence. Throughout

the country we've seen plenty of displays of this period told from the German

and South African perspective, and it was enlightening to see the viewpoints

of the indigenous cultures being told.

Less than a block away from the Christuskirche is the Alte

Feste, the oldest building in town (1890) and originally the headquarters

of the Schutztruppe, the colonial German defense force. Now the Namibian

State museum, the Alte Feste houses an excellent chronicle of Namibian history

starting just before the country's tenure as a German colony, through the

South African occupation, and ending with the advent of independence. Throughout

the country we've seen plenty of displays of this period told from the German

and South African perspective, and it was enlightening to see the viewpoints

of the indigenous cultures being told.

Many of the indigenous peoples didn't take the advent of colonialism lying down, most notably the Nama tribe lead by Hendrik Witbooi (left). Adopted by the current Namibian government as its central historical and cultural icon, Witbooi convinced his peoples and the Herero tribe to rebel against the colonial intrusion. Though Germany's support of the Namibian colony was tepid (the Kaiser thought it was a waste of time), the Schutztruppe were able to eventually overcome the rebellion and secure Namibia for Germany. Witbooi was able to win a type of autonomy and recognition of his tribe's lands, and made an uneasy truce with the Schutztruppe. This much is covered in all the historic discussions we've seen.

What all the prim, proper museums and textbooks don't discuss

is the human toll. The Herero had no such pragmatic leader as Witbooi, and

fought the colonialists to the bitter end. The Schutztruppe responded with

genocide against the Herero, wiping out 60,000 people, fully three quarters

of the tribe, and banishing the remainder to the Kalahari desert. Foreshadowed

in these old photographs lay the carnage of World Wars I and II.

What all the prim, proper museums and textbooks don't discuss

is the human toll. The Herero had no such pragmatic leader as Witbooi, and

fought the colonialists to the bitter end. The Schutztruppe responded with

genocide against the Herero, wiping out 60,000 people, fully three quarters

of the tribe, and banishing the remainder to the Kalahari desert. Foreshadowed

in these old photographs lay the carnage of World Wars I and II.

What puts it all in perspective is the realization that Germany is considered

one of the "good" colonial powers, that treated its African possessions

with a "gentle" hand. Makes one wonder what went on at the hands

of the Portuguese and the Belgiums, renowned as the severest of the European

colonialists. Little wonder that misery and death still stalk the lands

they once pillaged.

Enough of heavy reality -- it's time for a Brewery tour!

All that German influence wasn't totally negative, as Namibia is home for

what many consider southern Africa's and perhaps the continent's best beer:

Windhoek Premium Lager. Brewed according to the German Reinheitsgebot (of

course), it's the light and flavorable ale perfect for those hot African

days. They give tours, so we head on down and being the only ones that showed

up that afternoon we get a personalized excursion through the plant.

Enough of heavy reality -- it's time for a Brewery tour!

All that German influence wasn't totally negative, as Namibia is home for

what many consider southern Africa's and perhaps the continent's best beer:

Windhoek Premium Lager. Brewed according to the German Reinheitsgebot (of

course), it's the light and flavorable ale perfect for those hot African

days. They give tours, so we head on down and being the only ones that showed

up that afternoon we get a personalized excursion through the plant.

Our second brewery tour in Africa teaches us one unmistakable fact: beer

is a very big business here. We had hoped for some quaint brewery with a

hint of colonial trappings, only to find we're fully fifteen years too late.

They flushed that old downtown brewery years ago, replacing it with this

modern goliath of German brewing technology.

Turns out more than Windhoek is brewed here; they also are

the Namibian manufacturers of all Coke products, and also contract brew

Becks beer. The big news is that they soon will be producing Guiness as

well, relieving Namibia from being dependent on South Africa Breweries for

yet another import. Now, if they only brewed a Hefeweisen...

Turns out more than Windhoek is brewed here; they also are

the Namibian manufacturers of all Coke products, and also contract brew

Becks beer. The big news is that they soon will be producing Guiness as

well, relieving Namibia from being dependent on South Africa Breweries for

yet another import. Now, if they only brewed a Hefeweisen...

We're afraid to say, but this visit cured us of the need to visit any

more breweries in southern Africa. Mega is the theme in beer and alcohol

here, and the small breweries we've come to love in California simply don't

exist. Much as it was in America some twenty years ago.

Swakopmund

From Windhoek we drive west towards the coast and into the

world's oldest desert - some eighty million years old. Unique as the only

desert that meets the ocean, the Namib lies all along the coast and extended

several hundred kilometers inland. This brutal buffer made this portion

of Africa undesirable to European explorers and is the main reason why Namibia

was one of the last places colonized in Africa.

From Windhoek we drive west towards the coast and into the

world's oldest desert - some eighty million years old. Unique as the only

desert that meets the ocean, the Namib lies all along the coast and extended

several hundred kilometers inland. This brutal buffer made this portion

of Africa undesirable to European explorers and is the main reason why Namibia

was one of the last places colonized in Africa.

We stay in the old German settlement of Swakopmund. Now the premier beach resort in Namibia, we've landed smack dab in the middle of prime fishing season. Here in southern Africa people time their summer vacations to co-incide with the month-long school Christmas break (this year: Dec 13th - Jan 14th), when they set out en masse and pack all the holiday resorts and sights. It's as if you combined the northern hemisphere's August holiday crunch with the Christmas frenzy. Already we've noticed a dramatic increase in the number of tourists where ever we go.

Fortunately, we're here for only a few days before traveling north. Among

the sights we see is an ancient steam tractor called the Martin Luther,

abandoned in the desert where it last gasped. An example of how European

technology failed once it smacked up against Africa, it's so named after

a quote from one of Luther's speeches: "Here I stand. May God help

me, I cannot do otherwise."

Just south of Swakopmund lies the northern portion of the

Namib-Naukluft Park and some of the most dramatic desert terrain we've seen

on our trip so far. This photo to the right shows part of the desert they

refer to as the moonscape. Only on the surface does this desert look as

barren as the moon; a few hours here and one gradually becomes amazed at

the amount of life here. Lichen grows everywhere, watered by the ocean fog

that drifts over the coastal edge of the Namib.

Just south of Swakopmund lies the northern portion of the

Namib-Naukluft Park and some of the most dramatic desert terrain we've seen

on our trip so far. This photo to the right shows part of the desert they

refer to as the moonscape. Only on the surface does this desert look as

barren as the moon; a few hours here and one gradually becomes amazed at

the amount of life here. Lichen grows everywhere, watered by the ocean fog

that drifts over the coastal edge of the Namib.

Geologically, the Namib is a fascinating place with its tumbled

and crumpled crust. Many of the rocks are colored from the minerals present

in them, painting the desert a dozen shades of tan, ochre and weathered

copper. Huge veins lie exposed throughout the hills; take a gander at this

wide layer of dolomite streaking the hills to the left.

Geologically, the Namib is a fascinating place with its tumbled

and crumpled crust. Many of the rocks are colored from the minerals present

in them, painting the desert a dozen shades of tan, ochre and weathered

copper. Huge veins lie exposed throughout the hills; take a gander at this

wide layer of dolomite streaking the hills to the left.

The weather on this Friday afternoon is typical for the Namib: dry and

hot. With no clouds in the sky, the sun combined with the southern pole's

feeble ozone layer stings our skin like needles whenever we venture out.

Even locals hide in the shade of trees and buildings. Work usually stops

during the height of the day, resuming once the sun settles lower in the

sky.

One plant species, although common from southern Namibia

all the way north into Angola, dominates this section of the Namib. The

Welwitschia manages to prosper in a place few other plants and animals can

survive. Actually a conifer, this tree has radically adapted itself to the

harsh desert environment and can live to be a very old age. This one to

the right is believed to be 1500 years old, and several are known to be

over 2000 years old.

One plant species, although common from southern Namibia

all the way north into Angola, dominates this section of the Namib. The

Welwitschia manages to prosper in a place few other plants and animals can

survive. Actually a conifer, this tree has radically adapted itself to the

harsh desert environment and can live to be a very old age. This one to

the right is believed to be 1500 years old, and several are known to be

over 2000 years old.

The Welwitschia actually has only two leaves, though the

fierce Namibian winds shred them so that it appears to have many ribbonlike

leaves. With leaves that feel as if they're made of tin and a trunk that

feels like iron, the Welwitschia speaks to the extremes both plants and

animals must go to in order to survive in the Namib.

The Welwitschia actually has only two leaves, though the

fierce Namibian winds shred them so that it appears to have many ribbonlike

leaves. With leaves that feel as if they're made of tin and a trunk that

feels like iron, the Welwitschia speaks to the extremes both plants and

animals must go to in order to survive in the Namib.

Skeleton Coast

Leaving Swakopmund, we take the coastal road north that all the maps label as unpaved. True enough, but this road is not just dirt but some sort of hard-packed alkali mud that is as hard as cement. The few small towns and settlements we pass are truly bleak places, scratched out of the surface of this unforgiving collision of desert and ocean.

Traveling oftentimes throws one for a loop, taking something

familiar and twisting it into the exotic. Living in San Francisco makes

seals part and parcel of the background of your life, and as such we didn't

feel we would be all that impressed with the colony of seals at Cape Cross.

We were not prepared for what we saw. On a single small prominence into

the Atlantic ocean was this incredible colony of seals, a quarter million

in number.

Traveling oftentimes throws one for a loop, taking something

familiar and twisting it into the exotic. Living in San Francisco makes

seals part and parcel of the background of your life, and as such we didn't

feel we would be all that impressed with the colony of seals at Cape Cross.

We were not prepared for what we saw. On a single small prominence into

the Atlantic ocean was this incredible colony of seals, a quarter million

in number.

Even before we saw the seals themselves we knew this was going to be

weird. One hears the barking of the seals at a distance, though we found

it difficult to discern exactly what the din was. As you walk to the edge

of the viewing wall, you get slammed by this repulsive fish and shit stench.

A smell you never really get used to, the slime left by the thousands of

seals make it difficult as you are drawn closer to see the colony.

November and early December are the birthing

months, and it was our dubious fortune to catch the colony as it coped with

the tens of thousands of seal pups. Seal pups were being born and dying

right before our eyes. Scavenger birds peck around the edges, feasting on

the freshly dead pups.

November and early December are the birthing

months, and it was our dubious fortune to catch the colony as it coped with

the tens of thousands of seal pups. Seal pups were being born and dying

right before our eyes. Scavenger birds peck around the edges, feasting on

the freshly dead pups.

While there were lost and sorrowful pups wandering crying for their mothers, most pups were huddled in nurseries such as the two in the photo to the right. Several cows care for dozens of cubs as their mothers head out to sea to feed.

Cape Cross is historically famous as the point where Diaz left a cross

on his first voyage to the southern tip of Africa, but that cross was overshadowed

by the seal colony. It's a sight we won't soon forget.

We camp that evening at Mile 108. Many of the names along

the Skeleton coast come from how far these places are north of Swakopmund.

As we slept, a few of our friends in San Francisco embarked on a "Where's

Gagnon" pub crawl. Perhaps they thought Jim was lost, passed out in

some pub somewhere. At any rate, at midnight San Francisco time Jim toasted

those intrepid pub crawlers, perhaps the first time this trip where he had

a beer before the morning's first coffee.

We camp that evening at Mile 108. Many of the names along

the Skeleton coast come from how far these places are north of Swakopmund.

As we slept, a few of our friends in San Francisco embarked on a "Where's

Gagnon" pub crawl. Perhaps they thought Jim was lost, passed out in

some pub somewhere. At any rate, at midnight San Francisco time Jim toasted

those intrepid pub crawlers, perhaps the first time this trip where he had

a beer before the morning's first coffee.

While some loose sources describe the entire coast of Namibia

as such, the Skeleton coast of mariner lore starts just north of Swakopmund

and reaches up into southern Angola. Notorious for the Benguela current

that fought the European spice ships sailing for the orient, and for a desolate

coastal desert that finished off the crews of the ships waylaid by the current's

frigid punch, a flavor of hell manifests itself here on Earth. Preserved

as a park of which only one third is open to the general public, we saw

the Skeleton Coast on some good days. A high and light fog shrouded us of

the sun's worst, allowing us and the animals painless access during the

daylight hours.

While some loose sources describe the entire coast of Namibia

as such, the Skeleton coast of mariner lore starts just north of Swakopmund

and reaches up into southern Angola. Notorious for the Benguela current

that fought the European spice ships sailing for the orient, and for a desolate

coastal desert that finished off the crews of the ships waylaid by the current's

frigid punch, a flavor of hell manifests itself here on Earth. Preserved

as a park of which only one third is open to the general public, we saw

the Skeleton Coast on some good days. A high and light fog shrouded us of

the sun's worst, allowing us and the animals painless access during the

daylight hours.

Bones of animals, whales, ships, trucks, and towns all lay

strewn along our drive north. The only kind of skeleton we didn't see in

the park were human -- we hear they pick those up. The fishing vessel once

called "The Seal" wrecked in 1976 gives an idea of the debris

you find along the Skeleton Coast.

Bones of animals, whales, ships, trucks, and towns all lay

strewn along our drive north. The only kind of skeleton we didn't see in

the park were human -- we hear they pick those up. The fishing vessel once

called "The Seal" wrecked in 1976 gives an idea of the debris

you find along the Skeleton Coast.

We stayed one night in the park at a campsite that is only open a month

and a half each year: Torra Bay. Normally to stay overnight this far north

in the park you must get a cabin at Terrace Bay, but during prime fishing

season they open up a low impact camp and we snatched a spot there. Not

our normal camping scene, we found the camp's dozen or so gasoline generators

used to power peoples' refrigerators annoying.

Apparently the west coast of Africa hosts a large late winter

whale migration from Cape Town all the way north up the coast. Many don't

make it, and a few of those wash up on the shores of the Skeleton coast.

Their jaw bones make passable benches and gates, eh?

Apparently the west coast of Africa hosts a large late winter

whale migration from Cape Town all the way north up the coast. Many don't

make it, and a few of those wash up on the shores of the Skeleton coast.

Their jaw bones make passable benches and gates, eh?

As always, for there to be this much death in a place it

must first be crawling with life. The Benguela current may rob the coast

of rain and bring desolation to the land, but it also feeds a tremendous

marine ecology, and the animals that dine off of the ocean prosper here.

An example we spied early one morning illustrates this; several thousand

cormorants take their time migrating north, working the Skeleton coast for

meals and rest.

As always, for there to be this much death in a place it

must first be crawling with life. The Benguela current may rob the coast

of rain and bring desolation to the land, but it also feeds a tremendous

marine ecology, and the animals that dine off of the ocean prosper here.

An example we spied early one morning illustrates this; several thousand

cormorants take their time migrating north, working the Skeleton coast for

meals and rest.

A loop through the North

Turning inland from the coast we find that oddities abound

in the Namibian desert. The welwitschias are back, as are the ostriches

and gemsboks. We've decided to spend the next few days bouncing around in

the heat checking out the touron's curiosities in our path. At times we

feel as if we're traveling across the American western desert, with all

the sights set up, sign-posted, and developed. Not too surprising, as most

of the tourists' points of interest were set up during the years that South

Africa administered Namibia. Namibia was and still is a prime vacation spot

for South Africans, and their motor culture places many of the same demands

as America's does on the desert.

Turning inland from the coast we find that oddities abound

in the Namibian desert. The welwitschias are back, as are the ostriches

and gemsboks. We've decided to spend the next few days bouncing around in

the heat checking out the touron's curiosities in our path. At times we

feel as if we're traveling across the American western desert, with all

the sights set up, sign-posted, and developed. Not too surprising, as most

of the tourists' points of interest were set up during the years that South

Africa administered Namibia. Namibia was and still is a prime vacation spot

for South Africans, and their motor culture places many of the same demands

as America's does on the desert.

The route we've chosen drops us at a point called Twyfelfontein

(Afrikaans for "doubtful fountain") for the evening. Before setting

up camp, we tour the 6000 year old petroglyphs nestled among the rock cliffs.

Bone dry but for a single small fountain that produces a meager cubic meter

of water a day, Twyfelfountein was a favorite overnight stop for the ancient

San hunters, and they documented their expeditions by engraving the cliff's

sandstone faces.

The route we've chosen drops us at a point called Twyfelfontein

(Afrikaans for "doubtful fountain") for the evening. Before setting

up camp, we tour the 6000 year old petroglyphs nestled among the rock cliffs.

Bone dry but for a single small fountain that produces a meager cubic meter

of water a day, Twyfelfountein was a favorite overnight stop for the ancient

San hunters, and they documented their expeditions by engraving the cliff's

sandstone faces.

Some engravings are positioned in shady, out-of-way places and bored

guides take you through pointing out the more interesting ones (below).

The sculptured landscape alone would be interesting, but with ancient drawings

one's reward, climbing about is loads of fun.

Normally, a sight such as Twyfelfontein would deserve a "drive

by" visit, but Lonely Planet declares the local campsite Aba-Huab as

Namibia's finest overnight camp. We left wondering who the author slept

with, as we found it a fly-plagued and decidedly second rate experience.

Normally, a sight such as Twyfelfontein would deserve a "drive

by" visit, but Lonely Planet declares the local campsite Aba-Huab as

Namibia's finest overnight camp. We left wondering who the author slept

with, as we found it a fly-plagued and decidedly second rate experience.

Near Twyfelfontein lies a unique rock formation alone worth

the visit to this area. Called the Organ Pipes, this vertical shaft of dolorite

takes on a cubist's impression of a church organ. This photo shows only

a small section of the dry riverbed lined with these pipes of rock.

Near Twyfelfontein lies a unique rock formation alone worth

the visit to this area. Called the Organ Pipes, this vertical shaft of dolorite

takes on a cubist's impression of a church organ. This photo shows only

a small section of the dry riverbed lined with these pipes of rock.

Down the road from the Organ Pipes is a true bust of a sight: burnt mountain.

Not a mountain at all, it's hardly a hill of some black and burnt appearing

material. However, the quartz field across the road amused us for a while.

We had never seen such an expanse of quartz before.

The next morning we continued inland through some truly arid

landscape. Locals we talked to tell us it has been years since they've seen

rain. This strikes us as odd, as over only a few ridges lies Outjo where

plenty of rain found us as we dealt with a sick Land Rover. Our next tourist

attraction shows that this land once indeed saw much more rainfall in past

times. Namibia's petrified forest offered us a glimpse into the dance of

the eons of which we personally experience only a heartbeat.

The next morning we continued inland through some truly arid

landscape. Locals we talked to tell us it has been years since they've seen

rain. This strikes us as odd, as over only a few ridges lies Outjo where

plenty of rain found us as we dealt with a sick Land Rover. Our next tourist

attraction shows that this land once indeed saw much more rainfall in past

times. Namibia's petrified forest offered us a glimpse into the dance of

the eons of which we personally experience only a heartbeat.

While the state maintains a national park to preserve a section of the Petrified Forest, the extent of the fossils is much larger. Fully five kilometers of a now exposed ancient valley offered the proper conditions to form these stone snapshots of these long gone trees. Several "petrified forests" are open for a fee, and as they lack the strict regulations of the state park, one is free to snatch a few momentos of your visit.

It's believed that the original forest of gymnosperms didn't actually

grow here but rather was washed down to this valley in some ancient flood,

as there are only the trunks of the trees and none of their roots or branches.

Some trunks are massive, up to 34 meters long and six meters around. Most

are so well preserved that you can count their rings and discern wet and

dry years some 260 million years past.

On our road back to Outjo where we've decided to overnight

must be one of the oddest sights you'll find in a farmer's field. Vingerklip

is this curious pillar of weathered sandstone. Not long for this earth with

its eroded base, the column was an interesting enough sight by itself, but

we were both amazed at the valley it lay in and the surrounding mesas. No

hint of these can be glimmered from the roads that pass through this region,

and each passing dirt road and turn now make us wonder at what other strangeness

might lie at its end.

On our road back to Outjo where we've decided to overnight

must be one of the oddest sights you'll find in a farmer's field. Vingerklip

is this curious pillar of weathered sandstone. Not long for this earth with

its eroded base, the column was an interesting enough sight by itself, but

we were both amazed at the valley it lay in and the surrounding mesas. No

hint of these can be glimmered from the roads that pass through this region,

and each passing dirt road and turn now make us wonder at what other strangeness

might lie at its end.

Our last night in Outjo was a rainy

one, but pleasant enough as the town and its environs are now familiar to

us. Bidding Outjo and Bambi the kudu goodbye, we leave the north for the

last time and head back towards Swakopmund, where we plan on resupplying

before we head deep into the Namib desert. Along the way in another farmer's

field lies another one of those sights we hate to pass by: a set of dinosaur

footprints. A detour towards the town of Otjihaenamapareno down a set of

dirt roads muddied by last night's rains leads us to this ancient edge of

a long gone lake.

Our last night in Outjo was a rainy

one, but pleasant enough as the town and its environs are now familiar to

us. Bidding Outjo and Bambi the kudu goodbye, we leave the north for the

last time and head back towards Swakopmund, where we plan on resupplying

before we head deep into the Namib desert. Along the way in another farmer's

field lies another one of those sights we hate to pass by: a set of dinosaur

footprints. A detour towards the town of Otjihaenamapareno down a set of

dirt roads muddied by last night's rains leads us to this ancient edge of

a long gone lake.

On a exposed bed of sandstone captured by some geological magic lay this

small portion of an upright walking dinosaur's wanderings. Most of the prints

were muddied, worn away by the same processes that exposed them in the first

place, but two footprints showed very clearly a three-toed birdlike foot

of an animal with a stride length about the same as a man's. The sight makes

us both wonder if the earth will capture some faint whisper or echo of our

own personal existence perceptible some eighty million years hence.

Spitzkoppe

Turning South towards Swakopmund we unmistakably

learn that rain in Namibia is a feast or famine ordeal. We encounter a true

wall of water so thick we considered pulling off the road to try to wait

it out. We would have as well, if the sides of the road hadn't been totally

flooded by the sudden deluge. Dark, thick and heavy for about a kilometer

or so, and then it was gone. Past this stripe the land was dry.

Turning South towards Swakopmund we unmistakably

learn that rain in Namibia is a feast or famine ordeal. We encounter a true

wall of water so thick we considered pulling off the road to try to wait

it out. We would have as well, if the sides of the road hadn't been totally

flooded by the sudden deluge. Dark, thick and heavy for about a kilometer

or so, and then it was gone. Past this stripe the land was dry.

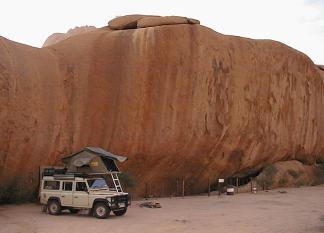

We pull up short of Swakopmund by about a hundred miles or so to spend an evening at the mountain referred to as the Matterhorn of Africa. Not nearly so tall, Spitzkoppe still towers over the sandy plains surrounding it. Administration of the Spitzkoppe and surrounding camps has been turned over to a local tribal co-op, giving the night's stay a decidedly African feel. Hope you brought water, and if you need to go better grab a shovel.

Camping like this truly is a joy for us. You immediately lose the crowd

that require a place into which to plug their fridge or empty their caravan's

toilet. We always travel set up to be able to survive on our own for about

a week, so a night is nothing. Only one other camper joined us that evening,

and they chose a camp on the other side of the mountain, leaving us alone

with the rocks and the stars.

Ours was the prime spot, next to the San

rock paintings that were at least two thousand years old. Camping here allowed

us to understand why Africans consider some rocky formations to be power

spots. The earth releases energy in places such as this, affecting all around.

Ours was the prime spot, next to the San

rock paintings that were at least two thousand years old. Camping here allowed

us to understand why Africans consider some rocky formations to be power

spots. The earth releases energy in places such as this, affecting all around.

We drove around the rest of the mountains and hills the next morning, and even tried some climbing. Too difficult for only shorts and hiking boots, we learned firsthand why Spitzkoppe wasn't climbed until 1945 despite it's meager 1728 meter height.

After Spitzkoppe we stopped at Swakopmund to resupply. The deep Namib

desert is next and we want to be prepared.